The Philadelphia Story

An innovative work program in the "real world"

Karen Byerly and Lynda Ford

In a period of Government cost-cutting, opportunities for Federal agencies to share resources in support of joint goals represent a good use of taxpayers’ dollars. For some years, the Federal Bureau of Prisons has been investigating new approaches to providing punishments for nonviolent offenders that are both appropriate and provide a smooth transition from prison to the community—allowing inmates to work in quasicommunity settings. In October 1990, the Bureau implemented a new form of alternative punishment that had been in planning since early 1989. The Philadelphia Urban Work Cadre program allows nondangerous Federal inmates, who are within 10 to 18 months of release and have good histories of institutional adjustment, to transfer to an Urban Work Cadre (UWC) program in a Community Corrections Center (CCC), where conditions are very restrictive. Cadre inmates perform jobs for another Federal agency—the Defense Personnel Support Center (DPSC). When Cadre inmates reach the last part of their sentences (normally, the last 6 months), they will move into the “prerelease” phase, where they live in a Community Corrections Center and work in traditional jobs in the community. Thus, the Urban Work Cadre Program provides an intermediate way station on the traditional “prison to halfway house” journey.

How the program began

The concept of a community-based intergovernmental work agreement was initially developed by former Northeast Regional Director Charles Tumbo and his staff, with strong support from Bureau Director J. Michael Quinlan. The program was not actually implemented until the spring of 1990, when General John K. Cusick, Commander of the Defense Personnel Support Center (DPSC) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, approached the current Regional Director, George C. Wilkinson, regarding the need for manpower on the base.

At the same time, the Greater Philadelphia Community Corrections Center (GPCCC), a Bureau of Prisons contract facility, was experiencing low population levels. The director of GPCCC was approached about the possibility of an Urban Work Cadre program, knowing the interest of General Cusick at the DPSC. GPCCC staff and their board of directors were receptive to the idea.

Under Title 18 USC 4125 (a), “the Attorney General may make available to the heads of several departments the services of United States prisoners under terms, conditions, and rates mutually agreed upon, for constructing or repairing roads; clearing, maintaining, and reforesting public lands; building levees; and constructing or repairing any other public ways or works financed wholly or in major part by funds appropriated by Congress.” This became the legal basis for the program.

Frequent meetings took place among Bureau, DPSC, and GPCCC staff between May and September 1990. An interagency agreement was developed between the Bureau and the DPSC that outlined responsibilities for each agency—basically, onsite supervision would be DPSC’s responsibility—and the type of work and supervision the inmates required:

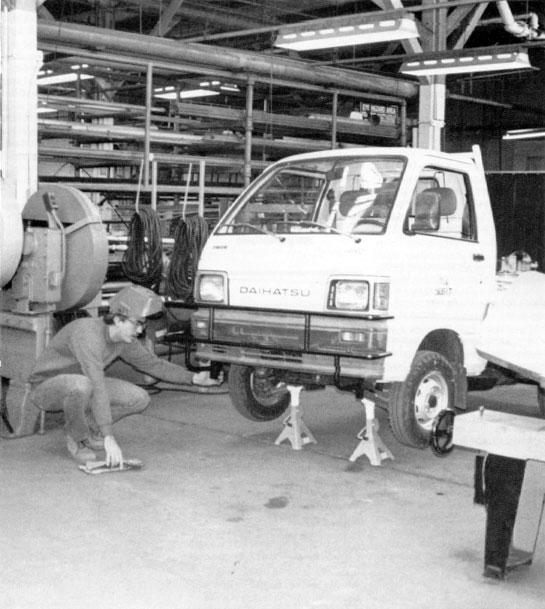

- Inmates would perform general maintenance duties on the military base—mowing lawns, painting, doing carpentry, cutting trees, performing custodial duties, and doing similar types of work.

- The Bureau’s Northeast Regional Office (NERO) in Philadelphia would select inmates to work on the base.

- NERO would ensure that inmates had no prior Department of Defense employment. n The use of Federal inmates would not be a substitute for available civilian personnel.

- Inmates would be paid from Bureau of Prisons performance pay funds. (All physically able Federal inmates work and are paid a modest wage, on a scale from $.23 to $1.15 per hour.)

- Inmates would be considered as serving in an industry, and thus would be covered for injuries under the provisions of the Inmate Accident Compensation System.

- The Bureau would cover transportation costs for inmates between the CCC and the work site.

- Inmates would comply with all DPSC rules and receive an orientation from base personnel.

- The CCC would ensure that at least four inmates had valid drivers’ licenses. n The base would provide 8 hours of work per day per inmate, as well as technical supervision, tools, equipment, and materials necessary to perform agreed-upon tasks. The base would allow for break and lunch periods.

- The base would provide periodic safety briefings to inmates.

- Inmates would be provided identification badges to be worn on base premises.

- The base would provide emergency medical care and notify the CCC of any accidents.

- The CCC would make weekly and asrequired onsite visits to substantiate attendance and discuss worker problems.

It was agreed that inmates chosen for participation in the GPCCC program would be medically cleared volunteers who had 10 to 18 months remaining on their sentences and were classified as minimum- or low-security. They would have no history of violence, organizedcrime participation, or serious drug use, and would have received no misconduct reports during incarceration.

The initial plan was to transfer 25 inmates from institutions in the Bureau’s Northeast Region to GPCCC for participation in the Urban Work Cadre Program. After several meetings with DPSC and GPCCC, it was decided the inmates would be placed into the program in staggered-arrival groups of 10, 10, and 5, to allow time for any necessary adjustments between arrivals. This proved to be a wise decision, and minor issues were resolved at each stage. On October 15, 1990, the first group of 10 inmates began the Philadelphia UWC program.

By January 1991, the phased implementation was complete; 25 inmates were working at DPSC. To date, 88 inmates have participated in the program. Fiftysix have successfully completed the program, resulting in referrals to the prerelease phases of their sentences. The program has had eight failures: five for drug use, one for being in an unauthorized area, one for failure to stand count, and one escapee.*

None of the program failures resulted from an incident “on the job” at DPSC. As for the participants who remain in the program, CCM staff receive outstanding reports regarding their capabilities, work performance, and behavior. One inmate was hired while still at the CCC, to work at DPSC in the Facilities Engineering Department.

Program development issues

Much of the program’s success depends upon the initial screening conducted by institutional Unit Management Teams (consisting of a unit manager, case manager, and correctional counselor) before submitting referrals. Unit staff must be knowledgeable regarding the UWC’s mission and criteria to successfully match inmates having the necessary physical ability or work skills to assignments at DPSC. Unit Teams must also make judgements regarding the suitability of an inmate’s temperament to perform work in a Federal agency and to reside in a CCC.

Upon arrival at GPCCC, program participants are briefed by CCC staff about Center living, and its rules and regulations. Then the community corrections manager (who has oversight of the program) and other CCC staff, along with the regional safety specialist, acquaint inmates with program guidelines.

As part of the inmate’s orientation phase, he is told he will be referred to as a “resident” rather than “inmate.” Psychologically, this helps the inmate begin the transition from prison to the community. This term also makes it easier for DPSC staff to relate to the program participants. DPSC staff show the residents a 20- minute slide presentation on the mission of DPSC, and give them a thorough briefing regarding conduct on the base.

A staff orientation package was developed to help the base supervisors deal with the residents. All DPSC staff who would be working with residents received the 2-hour orientation, which covers such topics as accountability, safety issues, equipment operation, transporting residents, performance evaluations, compromising situations, control of work crews, and escape procedures. A total of 25 staff were trained during October 1990.

One of the first programmatic issues addressed was that of social privileges for the residents. Upon initial arrival at the CCC, residents were permitted to walk in the community 45 minutes each day for exercise and recreation. Once the residents started work at DPSC, they were eligible for a 3-hour social pass each weekend during the first 30 days. After successful completion of the first month, the resident became eligible for 8-hour social passes every other weekend and 3-hour passes for the remaining weekends.

After further evaluation and review, the pass system was revised to the following:

- In program up to 30 days—4 hours per weekend.

- In program 31 to 90 days—12 hours every other weekend; 4 hours on remaining weekends.

- In program more than 90 days—12 hours per weekend.

During the early stages of the program, residents’ needs for routine outpatient health care, prescription refills, and dental care became apparent. A purchase order was approved for prescription medications to be acquired through a local pharmacist. A contract is pending for outpatient, inpatient, and prescription services with a local health care provider or a hospital for UWC residents, as the Bureau of Prisons continues to be responsible for their medical treatment. Once a resident transfers to the prerelease phase and is employed, the resident is responsible for his own medical expenses.

At first, the performance pay rate was $.40 per hour. As UWC participants, the residents had expenses not incurred when they were incarcerated—haircuts, personal hygiene items, and so on. (Items purchased in institution commissaries were less expensive than at local stores.) Due to these additional expenses, the performance pay was increased to $.75 per hour, which appears to be adequate.

A few weeks into the program, it became apparent that the residents would need additional protective clothing (jumpsuits) for the work they were performing at DPSC. Two jumpsuits were issued to each resident; winter parkas were also purchased for them by the Bureau.

Benefits of the program

In the 2 years it has been in operation, the Philadelphia UWC program has already provided a number of benefits:

- Enhanced partnerships between Federal agencies in a community setting.

- Job training and career counseling for residents through DPSC’s Office of Civilian Personnel—and the possibility of permanent employment.

- Opportunities for residents to demonstrate they can be trusted when given responsibility—thus promoting confidence in their ability to return to the community from a prison environment.

After 6 months of operation, an evaluation determined that the program was cost-effective, and DPSC indicated they could use an additional 2.5 residents. In March 1991, an agreement increased the UWC to 50 residents. In October 1991, DPSC requested that the Bureau reduce UWC employment to 35 during the winter months, as jobs such as landscaping and outside maintenance were not available.

Guidelines for future work groups

During the spring of 1991, a work group was appointed by the director of the Bureau of Prisons to develop guidelines for the expansion of community service projects. Operations Memorandum 225- 91 (Community Service Projects), dated October 9, 1991, was developed by the work group and outlines the following obligations for host Federal agencies:

- Providing transportation of inmates to and from the work site.

- Providing special protective and safety equipment, materials, tools, and supplies not normally available to inmates at the institution.

- Providing supervision of the inmate workers. Supervisors are required to be trained by the Bureau under the policy requirements for volunteer/contract workers. Supervision requires visual contact with inmates at least every 2 hours. The host agency will maintain inmate accountability through the use of inmate work detail cards furnished by the Bureau.

- Ensuring that supervisors are of good character, do not have significant criminal records (the degree of significance is decided at the local level between the institution and host agency), and have no histories of drug or alcohol abuse.

- Submitting monthly work reports on each inmate to the Bureau. Safety talks are required at least once per week. Unusual events, such as escapes or inmate misconduct, must be immediately reported to Bureau officials.

- Providing a safe and humane working environment.

- Providing emergency medical care and attention, with immediate notification to the Bureau of any such care or additional inmate needs.

In turn, the Bureau assumes the following obligations:

- Performing appropriate screening for nondangerous candidates.

- Selecting the inmates capable of performing work as required.

- Providing regularly scheduled meals.

- Providing inmates with work clothing and safety shoes.

- Providing training to host agency employees.

- Providing a project representative who will visit the work site at least weekly.

- Providing all inmate pay and jobperformance incentives.

- Reimbursing medical expenses for emergency and other necessary treatment of the inmates.

Qualifications for the program have changed in two major areas. Initially, the Bureau utilized only inmates transferring from an institution for participation in the program. The Bureau is now emphasizing the use of urban work camps as an intermediate punishment for offenders sentenced directly from the court. This option provides a valuable tool for judges in selected, appropriate cases at the low end of the Federal sentencing guidelines.

The other major change was in the referral criteria concerning institution conduct. The original criteria required an inmate to maintain a clear institutional conduct record; however, institution staff may now refer an inmate for transfer to this program if he/she has not received an incident report during the preceding 12 months.

Service projects are to be developed by the chief executive officer (CEO) of the institution (the community corrections manager is considered a CEO) and submitted to the regional counsel to ensure compliance with legal requirements. The CEO will implement letters of agreement with the host agency after approval by the regional director.

The policy also requires the inmate to agree to sign the “Conditions of Residence in an Urban Work Camp.” This outlines obligations for inmates and expectations for them to pay for expenses related to their daily needs, with the exceptions of housing, meals, and bed expenses. In addition, each participant consents to urinalysis or other testing to detect unauthorized drug or alcohol use.

As a result of the success of the Philadelphia UWC program, the Bureau identified a strategic initiative for each region to develop a UWC program during Fiscal Year 1992. During the year, the six regional directors entered into agreements with other Government agencies to provide inmate labor under the provisions of Title 18 USC 4125(a). Currently, 11 UWC’s are operating in different areas of the country.

For instance, on January 7, 1992, an agreement was signed in the Northeast Region with the Naval Aviation Supply Office (NASO) for 20 female residents to work in that agency. Work release (CCC) housing is provided by Bucks Work Release Center through an intergovemmental agreement with the U.S. Marshals upon which the Bureau of Prisons “piggybacks.” The Bureau’s first female UWC program began operations on February 5, 1992.

Most recently, in October 1992 the Bureau signed an agreement with the National Park Service that will allow Federal inmates to perform maintenance and other work on Park Service facilities-constructing and repairing roads; clearing, maintaining, and reforesting public lands; building levees; and performing routine work such as mowing lawns and painting. The Park Service agreement is similar to previous agreements signed with the U.S. Veterans Administration and the U.S. Forest Service; the Bureau also has active projects with the National Guard and has considered pilot programs with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Urban Work Cadre programs—and interagency agreements such as that with the National Park Service—have a great deal of potential in a time of tightening Federal budgets, when agencies are concerned with maintaining the service levels of the past. For the agencies, the benefits are obvious; for the inmates, the experience of “real-world” work expectations is just as beneficial. The Philadelphia program points the way to future “win-win” partnerships in this area.

*The inmate who escaped has been returned to custody.

Karen Byerly is Associate Warden for Programs at the Federal Correctional Institution, Allenwood, Pennsylvania, and was formerly Community Corrections Administrator in the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ Northeast Regional Office. Lynda Ford is Community Corrections Manager at the Philadelphia Community Corrections Management Center.

Originally published in Federal Prisons Journal - Fall 1992